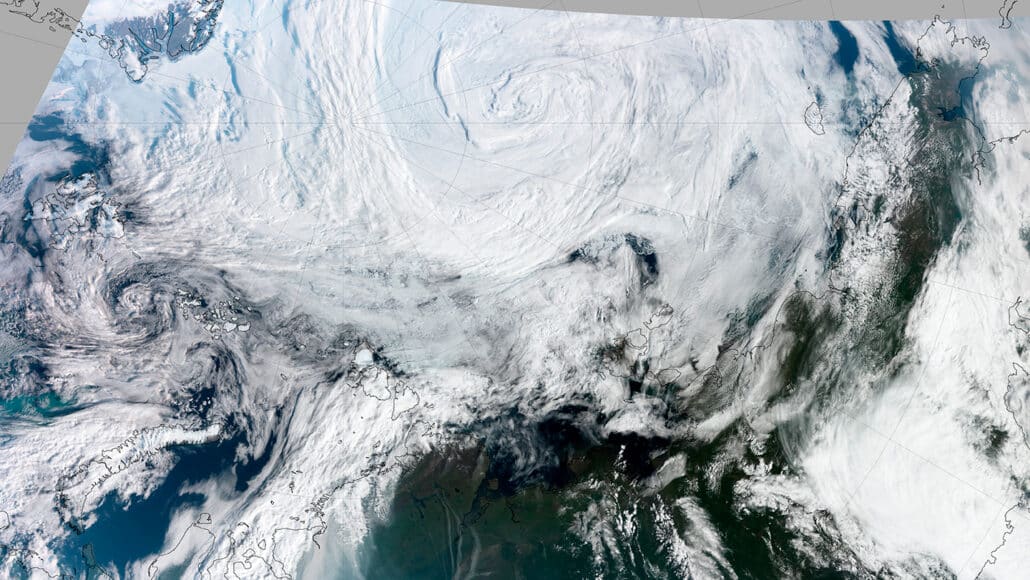

CHICAGO – In January 2022, a broad swath of ice-covered water between Greenland and Russia was devastated by a storm. The region’s terrible flotillas of sea ice were pummelling by 8-meter-tall waves. These waves churned up by fierce winds, as warm rain and southerly heat bombarded them from above.

Six days after the attack began, over a quarter, or around 400,000 square kilometres, of the huge area’s sea ice had melted, resulting in a record weekly loss for the region.

The storm is the strongest cyclone ever recorded in the Arctic. Yet, this may not be the case for very long. Arctic cyclones are intensifying due to climate change, with stronger winds, temperature fluctuations, and precipitation, according to Xiangdong Zhang, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Read More: Rubina Ashraf Criticizes Alizeh Shah’s Acting Skills

Accelerated Arctic warming and increasing storm intensity

The Arctic Circle is warming approximately four times faster than the remainder of the planet (SN: 8/11/2). Loss of sea ice owing to human-caused climate change is an important factor. The floating ice reflects far more solar radiation back into space than do bare oceans, altering global temperature (SN: 10/14/21). During August, the peak of the sea ice melting season, it has been observed that cyclones exacerbate sea ice loss, hence worsening warming.

Furthermore: Although hurricanes can devastate places further south, boreal vortices can endanger Arctic residents and travellers (SN: 12/11/19). If the storms intensify, “stronger winds pose a risk to sea transportation by generating bigger waves,” adds Vavrus, “and for coastline erosion, which has already become a serious issue throughout most of the Arctic and has prompted some towns to consider migrating inland.”

Farther south, climate change is strengthening storms (SN: 11/11/20). Yet, it is unknown how Arctic cyclones may change as the planet warms. Previous studies indicated that, on average, the core pressures of Arctic cyclones have decreased during the past few decades.

“Lower pressures often cause more violent storms with stronger winds, greater temperature fluctuations, and more rainfall and snowfall,” explains Xiangdong Zhang, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Zhang stated at the meeting that contradictions amongst analyses prevented a clear pattern from emerging. Therefore he and his colleagues compiled a thorough record of Arctic cyclone timing, strength, and length from 1950 to 2021.

In recent decades, Arctic cyclone activity has increased in intensity and frequency. It was documented by Zhang. In the 1950s, pressures in the cores of today’s boreal vortices were approximately 9 millibars higher.

Read More: Pakistan Records 73 New COVID-19 Cases in 24 Hours

In terms of context, such a shift in atmospheric pressure would be roughly similar to elevating a powerful category 1 storm into category 2 area. And during winters in the North Atlantic Arctic and summers in the Arctic north of Eurasia, the frequency of vortices increased.

According to U.S. Naval Research Laboratory meteorologist Peter Finocchio in Monterey, California, August cyclones are more damaging to sea ice than in the past. He and his colleagues studied northern sea ice and summer cyclones in the 1990s and 2010s.

Warmer water rising from below may have caused a 10 percent average loss in sea ice area following August vortices in the latter decade, compared to a 3 percent average loss in the earlier decade. Resulting in melting the ice pack’s underbelly, and by winds forcing the thinner, more mobile ice about, according to Finocchio.

Spring Storms Are More Dangerous

Climate scientist Chelsea Parker stated that cyclones in the Arctic may continue to intensify. Even during spring due to climate change. This could lead to a problem as the resulting vortices could increase the likelihood of sea ice melting in later summers.

Parker and colleagues simulated spring cyclones under varying climate conditions and discovered peak wind rising from 11 km/h to 60 km/h. They also observed these storms may persist at peak intensity.

The diminishing sea ice cover in the Arctic may fuel these storms, allowing them to penetrate deeper into the region. Parker will research Arctic cyclones in other seasons to grasp their future evolution under climate change. However, it’s unclear how society will cope with the intensifying storms.